In February 2023, I penned an article for ‘The Elelphant’ online journal https://www.theelephant.info/opinion/2023/02/13/chatgpt-what-the-hype/ that drew a lot of attention and feedback. It was about the alarming fawning and hype over AI. Looking back on it today, I realize that this was actually a treatise on the decline of humanity and our collective denial of human purpose. The use of technology, dating back to the rudimentary use of levers, tools, weapons and the invention of the wheel. One uniform thread of principle runs through all these developments. The tools and technology were ALWAYS a means to easier achievements of certain objective EXTERNAL to the tools themselves. For examples, weapons were to defend against threats, or eliminate competition that presents an obstacle to achieving some vital need. Fast forward to the 21st century, and after centuries of technical progress, technology ITSELF has become so profitable that it is becoming an end in itself. Weapons moved from being tools to win wars to being reasons for the same. Wars are now waged to sell and dispose of costly weapons that cannot be used in any way. In intellectually and spiritually weaker societies like Kenya, it has also taken on the aroma of a ‘cult’, with statements like “We’re a digital government” or “AI is the future”, not to mention the strange belief that apps and startups constitute ‘idea’ or ‘innovation’. Worst of all, it has accelerated the application of engineering solutions to human problems. In government, the digitization of financial systems (through IFMIS) for example, has led to levels financial looting unheard of in the ‘analogue’ era, and the thieves are never unmasked. Even the Government itself has found an excuse (“computer error”) for graft. Computers don’t err. Humans are the ones who conspire. Personally, I have found myself in situations where I waste untold hours of time on machines and tech to achieve very petty goals. I have logged into intricate digital platforms to see my child’s school report that could have been emailed to me, or even sent by whatsapp. Safaricom customer care no longer features any human being, and is about as helpful as the warts on a warthog’s snout. I have been teaching an advanced professional course online and my client is having these busy professionals log into a highly complicated system to upload their assignments which I can only mark by wasting even more time logging into the system. I couldn’t get any answer as to why these assignments couldn’t be emailed to me. And I have to waste even more time with the tech support person every day dealing with glitches. In other classes, I have seen students go online and produce a whole page of chat GPT generated drivel complete with references, when all I asked for was a 3-sentence paragraph of their thoughts on an issue. The list is endless. Self-driving cars, AI option for comments on social media, etc, etc…Our global environmental policies are based on AI generated climate models, and were willing to kill real humans to achieve what those brainless models demand of us. Part of the challenge is that the world is producing an entire ilk of humanity whose whole purpose is tech, and not the logical application thereof, and they are inspired by the huge sums of money made through this decline in human intelligence, not knowing that they are the commodity. Again, these tech “weeds” find fertile ground in intellectually stunted societies everywhere. Here’s the strongest evidence: Our president giving AI- generated speeches at times of crisis, and our top university starting a school of AI, inspired by a charlatan chancellor. I wonder if they will official accept chatgpt generated theses and fees payment in cryptocurrency. Retain your logic and qualitative thought. Human Society deserves it.

The misplaced arrogance of western academia when dealing with scholars from the global south

We are in a situation of oppression by outsiders interested in extracting the knowledge we have without caring about who we ARE. This string of emails is a small demonstration of what insurgency looks like. There is at least one African scholar who won’t take this any more;

From: XXXXXXXX>

Sent: Friday, February 9, 2024 1:56:03 pm

To: mordecai@ogada.co.ke <mordecai@ogada.co.ke>; mordecai.ogada@csa.or.ke <mordecai.ogada@csa.or.ke>

Cc: XXXXXXXXXXX>

Subject: Invitation to Geography Seminar Series, University of Sheffield

Dear Dr. Mordecai Ogada,

We’re writing to you as the convenors of the Human Geography seminar series in the Department of Geography, University of Sheffield, UK. We’d like to invite you to present your research at a seminar for our staff and students in 2024. If you’re interested, we’d like to offer you the opportunity to present online.

Our seminar series is a key part of the research culture of the department and draws an audience of postgraduate students and staff. Seminars are typically around 1.5 hours long and held on Wednesday afternoons/ lunchtimes, which we find works well for attendance.

The dates we have available are: May 1st or May 22nd 2024. Do let us know if one of these works for you. Any questions, please let us know!

Best wishes

XXXXXXX

On Fri, 9 Feb 2024 at 18:25, <mordecai@ogada.co.ke> wrote:

Hi XXXX, thanks for your message and the invitation. However, I don’t think an online lunchtime talk is a platform worthy of my academic engagement with the University of Sheffield, given the depth and breadth of my work over 25 years. I would rather be invited for a structured lecture visit where I can give a few lectures and engage with your students and faculty. In that way, I can also gain academically/ professionally, unlike an online lecture, which is a one-sided exercise, beneficial only to the university.

Regards

Mordecai

Sent from Outlook for Android

From: XXXXXXXXX>

Sent: Wednesday, February 14, 2024 6:19:31 pm

To: mordecai@ogada.co.ke <mordecai@ogada.co.ke>

Cc: XXXXXXX>; mordecai.ogada@csa.or.ke <mordecai.ogada@csa.or.ke>

Subject: Re: Invitation to Geography Seminar Series, University of Sheffield

Dear Mordecai,

Thanks for your response. We understand your position and we regret to say that we’re unable to offer you a structured lecture visit.

The scope of our seminars are designed for a small group of staff and students – because our department is small – who are interested in your field. We understand if that’s not amenable to you. However should you be interested, we are able to offer you a £50 fee for the recognition of your engagement and time spent preparing.

Thanks

XXXXXXXXX

Dear XXXXXX, I’ve read this message a number of times, and I am still baffled at how to deal such an insult. My conclusion is that you don’t think I am worthy of a structured educational engagement, because I am sure that the university of Sheffield does have visiting scholars. I would understand if your email even suggested that we try and find funding to do it sometime later, but you didn’t, because to you, what I may have to share academically is only worth lunchtime entertainment, when nobody has anything better to do.

Secondly, what do you think/ expect me to do with 50 quid?🤣 kudos, I didn’t think it was possible to make your message more ridiculous, but you did. At UK labour costs, If the tap in the lunch room was leaking, would £50 get a plumber to fix it? Anyway, I have some material for my ongoing blogs about disrespect for scholars from the global south by westen universities. I don’t know what ilk of academics you are, but next time, do listen to yourselves.

Mordecai

Sent from Outlook for Android

Excuse me Massa, Please don’t do that.

Having taken some time to think about the shameful breach of National Park Rules by Egyptian Diplomats, here’s my take; The Gods of our ancestors must be very averse to bullshit, because they never hesitate to insult purveyors of the same. After years in the conservation field, some of us know Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) Park rules by heart. Speed limit is 40 kmh, but they allowed WRC rally cars to do 180kmh because they are “white” (read: not local). They recently tripled park fees to keep out the “black” (read; local commoners) who were becoming too numerous in the parks. Now the “white” (foreign/ elites) that KWS loves so much have started misbehaving in the parks and the Director is breaking wind and fouling the atmosphere in his office. These people aren’t fools to endanger themselves, and many of them carry guns. If the lions approached them, I am sure it would have been a more serious incident of human-wildlife conflict. Locals do not behave recklessly in parks because we respect Wildlife and of course, punishment for any transgression would be swift and harsh. However, KWS is seeking to keep us out because “Out of Africa”, “Tarzan” and “The lion king” don’t include black people and our presence there diminishes the romantic quality of the product. In retrospect, I fully understand the disrespectful behaviour of the Egyptian diplomats. Why on earth does KWS expect foreign tourists to behave themselves, when at every turn, we demonstrate to them that they are exempt from the rules?? What am I missing? They know their position in “Magical” Kenyan safari tourism. As for KWS, until you can understand that WE Kenyans OWN this natural heritage and you’re our servants stewarding it for us, you can cry me a river. You have made parks “white” spaces, so stop interfering with the conduct of white people there. Kindly inform the DG to open the windows before any guests come to his office.

Writers are not ‘people who write’.

I have recently been receiving numerous invitations to write for various publications from people who rightly valued my work highly and treated it accordingly. It isn’t immediately apparent why, but this seems very specific to German clients from Newspapers, publishers and educational institutions. Typically it is “Dear Dr. Ogada, I am writing to you from XXXX, we are a publishing house/ periodical/ University press, and we would like to invite you to write an article of XXX words on the subject of XXX and we will pay you XXX for the assignment”. I get the impression that these invitations often come from people who know what it takes to do literary work, they are generally book publishing houses, newspapers and periodical magazines. Next is the British and American invitations, which are irritating in the way they seek to impress upon the writer that the ‘offer’ they are making is something of a privilege for you, yet they are unable to write it themselves. It is truly amazing how many people in publishing are so completely seemed unaware of the true value of what they purport to trade in. The term “Writing” itself is a very inaccurate reference to what writers actually do, because it describes the movement of the pen, or keys on a computer, but completely neglects the intellectual work, which is the core of the said activity. It is like referring to Michael Soi as a “Painter”, rather than a sage who communicates through painting. There is no greater indication of mankind’s intellectual decline than the reference to serious intellectual work by its physical manifestation. The most difficult part of this conundrum is dealing with fellow Africans who try so hard to be ‘white’ in the way they handle our intellectual outputs. I recently quit a socio-political analysis contract because of the ‘violence’ of their editorial processes. I had to fight every single month because the people purporting to ‘edit’ my work either didn’t understand what I was saying, didn’t believe what I was saying, or wanted me to change the way in which I was saying it. The articles came out as they did and were well-received in spite of, rather than because of the editorial process. I found myself in a situation where I was ‘defending’ articles in a manner akin to a postgraduate student defending a thesis, something that I found unacceptable, having last done so over 15 years ago. When did people forget that the skill of a writer is in his reading, or the skill of an artist is in his eye, just as that of a speaker is in his listening, or that of a singer in his ear?

Africa has a powerful oral tradition, rich in priceless idioms, proverbs and colloquial expressions, even within the confines of standardized foreign languages like English. That is why you can hear the ‘Luganda’ in Joachim Buwembo’s writing, the ‘Kikuyu’ in the late Wahome Mutahi’s writing, or the ‘Luhya’ in Ted Malanda’s prose. One of my favourites is Jerome Ogola, who writes unmistakable, fluent ‘African’ in impeccable English, despite being a child of many ethnicities between which he switches seamlessly.

Failure to accept that ‘colour’ in our expression is simply western vandalism, with no place in a civilized world. It is the literary equivalent of the looting of artifacts and destruction of African civilizations in the 18th and 19th centuries by European invaders. It is now time to civilize publishing by including the diverse scents, sounds, colours and beauty of Africa. For those who keep inviting me to publish in “peer-reviewed” journals, this is the reason why I consistently say ‘no’. It is a primitive structure, and I’ve outgrown it. I’m too civilized to do that stuff now. Read more material written in ‘African’. That’s where the truth about Africa resides.

Cranial Strength and Inner Peace

Make PEACE!

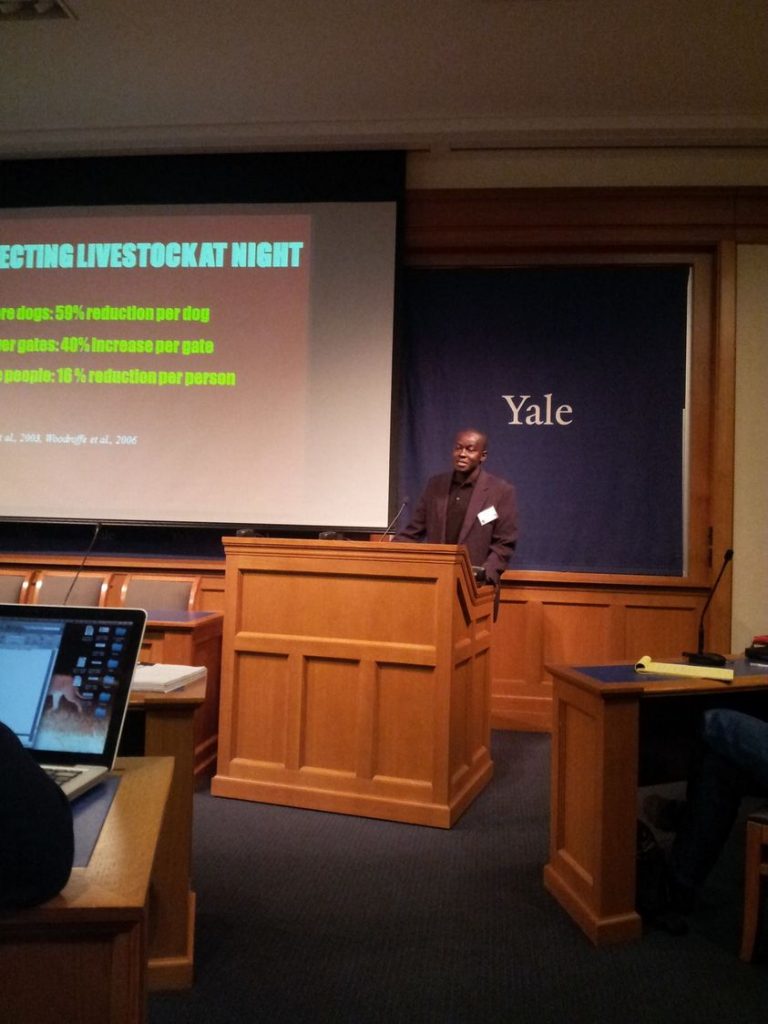

I am currently at a meeting hosted by a UN institution discussing biodiversity policy, targets and community rights in various contexts around the world. I am now old and qualified enough to throw shade or insult the UN amongst their officers (its strangely satisfying, but that’s a story for another day). Conservation and resource discourses have revolved for many decades around the ideas of old white men, so every meeting worth its salt that wants to maintain the status quo has what I call blackyouthgenderwashing. In simple English, it is an invited participant (often asked to speak) to make this nangsengs look good. The person needs to be young, black, or female (ideally all three, if the available resources can only afford to bring one invitee). Invariably these youngsters are enthralled by the opportunity afforded to them and feel the need to parrot the clichés of their benefactors. My attention has been drawn by one such young lady doing that here. I’ve had a long chat with her and told to “harden her cranium”. Luckily, she is from East Africa and could understand the Kiswahili syntax. Young people in this situation, you’ve been given a chance to make your mark: speak your mind! Here is the story I shared with her, because I am now old enough to speak plainly. One of my My MSc supervisors was a world-renowned carnivore ecologist. He was white, American and racist AF. I discovered this early in my research when we had an argument about research equipment, so I was baffled at why he recruited a student as black as me. After all he had been doing research in Kenya since the 1970s and had never had a black student. That’s when in a discussion with the project funder (AWF) I found out that he had received a grant that stipulated he must have an indigenous Kenyan student. That’s when I said OOOoooo!! (in a Dholuo accent) and ‘thickened my cranium’ to military helmet levels. I then made PEACE with the fact that I was a ‘blackwash’ and not a preferred student. I decided that I will never back down to him, and I will ‘kill’ the research project until he respects me. I also let him know that I don’t like him and I we would sit for hours driving across Laikipia in his single cab landcruiser pickup without me saying a word. I finished that MSc. 22 years ago and got my respect after publishing several papers, a book chapter and conference presentations from my work. We never spoke again after he signed my thesis. For the record, he’s never had another indigenous Kenyan student since I finished, so I suppose my skull also showed him things.

Young people always ask me whether they should take up scholarships or jobs with these racist conservation organizations or individuals. YES! Get in there, learn about them, do the job, but do not lose your soul. FOCUS on what your aspirations are and (if you don’t have a 32gb memory like mine) keep a diary of these transgressions and learn from them. At the right time, stand up and change things, or get out and fight like hell with the qualifications and information you have. Information is power, and those who have heard me speak truth to these people know that true power shuts people up. On the other hand, if you decide to follow the gravy train and become their kitchen toto, make PEACE with that and proceed accordingly. Don’t cry about being my “African brother” when one of my missiles hits you, because you are just collateral damage, which I have made PEACE with. When the racism gets too stifling, make PEACE with your kitchen toto status and don’t call me saying “nyefnyefnyef is going on, but I cant say anything because of my job, can you highlight it?” No, I won’t. You’re a kitchen toto, so don’t complain about the smell of onions, sawa? Young people in conservation; Make your decisions early enough in life, and make PEACE with it.

Worthless People: We Africans must learn our true value before trying to teach the world our values.

An ‘intellectual evolution’ of sorts has been happening over the last 2 decades, although may be a subjective view since I have viewed the period through the prism of my career as a conservation scientist. We are coming from a point of begging to be heard at international conferences at the turn of the century to a point today where resource conservation conferences are actively soliciting African input, and even being held in Africa in order to maximize on the same. Last year, we had CoP 27 in Sharm el Sheikh, Egypt and the Africa Protected Areas Congress (APAC) in Kigali, Rwanda. This year, there is the International Association for the Study of the Commons (IASC) conference in Nairobi. This is heralds a paradigm shift, because those of us with any involvement in resource economics are familiar with ‘The tragedy of the commons’. This theory developed in 1833 by British writer William Forster Lloyd refers to a situation in which individuals with access to a public resource (the ‘common’) act in their own interest and, in doing so, ultimately deplete the resource- An elegant definition of the nexus between capitalism and environment. Since then, individualist western thinking has abhorred the concept of commons and fought it relentlessly, so it what is changing, and how? The west is recognizing Africa’s resilience and the fact that its foundation is the various socio-cultural “commons” that exist in our continent.

This theory of course is based on the history of capitalism, which as I have written before, was the basis of imperial colonialism and its attendant cruelty. It also harks back to the epoch of primitive accumulation, when the perceived power of empires was largely material. Another much-used and primitive measure of empires was the geographical area over which they exerted their (often malevolent) influence, leading to grandiose statements like “”this vast empire on which the sun never sets, and whose bounds nature has not yet ascertained” Attributed to British colonial administrator George Macartney in 1773. This referred to the territorial expansion that followed Britain’s victory in the Seven Years’ war between the European powers over territories in the Americas, Asia and the Pacific. The state of human technological advancement at that time was such that this accumulation of material and the attendant power could be rooted advances in technical skills like maritime navigation or weaponry. “Soft skills” like trade negotiations and diplomacy, which necessarily required intellectual aptitude were used very peripherally (if at all) in the Europeans’ interactions with Africa. It was mostly extractive, capitalistic, and necessarily cruel.

The pedestrian quantitative view of Africa’s value today as solely material and largely based on our natural resources is at the core of our deepest external and internal intellectual challenges as a continent. Arguably the most harmful part of this challenge is the impact that it has on the thinking of our leaders. When those we entrust with power think that the best thing we can offer is material, then all their negotiations with the outside world become material-based and quantitative in nature, rather than value-based. Examples abound of the quantitative mentality and Kenya is one of the bastions of this this school of thought; We seek, for instance to earn more by exporting higher quantities of coffee, but not to roast, package, or otherwise add value to the product. We largely do the same with tea. In tourism, we constantly seek higher numbers of the much-vaunted ‘arrivals’ rather than the social and financial value they actually bring to Kenya. One former tourism minister even proposed waiving visa fees to make Kenya “more affordable”, leading one to wonder what financial value a country can gain from a tourist who cannot afford to pay fifty dollars. One apparent escapee from this mental ‘gulag’ is H. E. Yoweri Museveni, President of Uganda, even though his statements in this direction often escape notice or understanding. This first came to my attention from a post he made on Facebook™ in July 2015; “Human Resource is the greatest wealth, if it wasn’t, China would not be a rich country. It’s human resource that produces and consumes, minerals do not consume. That is how Japan, India and, even, South Korea have become much richer than Saudi Arabia. We need to integrate to create a wider market, and even have more produces (sic).” Following the general elections in Kenya, Mr. Museveni was invited to the inauguration of President William Ruto on 15th September 2022 and his speech included these words; “According to my experience of 60 years, I advise Africans that prosperity comes from wealth creation. And wealth is not the same as natural resources, you may have natural resources and not get wealth out of them…” It is true that the nations he named are wealthy, far beyond the material value of the material resources that exist naturally within their boundaries. Singapore is probably the most storied example of qualitative wealth generation out of value, rather than availability or ownership of material resources.

This is not a treatise for mutual exclusivity of these two bases, because the reality is far more sophisticated and demands that we approach it as such. Now that post-independence Africa trades with Europe in the same goods that were earlier looted, it is imperative that we do so under commercial and intellectual structures that differ from the exploitative ones they established to serve their colonial avarice. We need to adjust our philosophy away from seeking quantitative increase in trade volume to qualitative increase in trade value. This thematic shift is required across all interactions between Africa and the outside world from trade, education, philosophy, environmental issues and professional interactions, but I am able examine it most effectively through my lens as a scholar.

It goes without saying that Africa (like every other continent) is a constant spring of creative, scientific and technical ideas, but historically, very few of them have been exchanged or exported to other parts of the world. Instead, the African countries that like to look outward constantly gravitate to “bulk commodity” thinking, even when dealing with their citizens. In Kenya, human labour is becoming one one of our leading exports, earning the country Ksh. 502 billion (approximately 4 billion USD) in 2022. This is far ahead of our other commodity exports, which are typically agricultural. However, this is almost exclusively domestic workers, labourers, security personnel, hotel staff, valets etc. The government is very supportive of this trade, which is primarily done by agents under the kafala system, which exposes the workers to serious rights violations in their destination countries and an average of 80-100 homicides (mostly of women) annually, a grim figure in this day and age. The then Principal Secretary in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ambassador Macharia Kamau encapsulated our government’s attitude in this flippant response; “There are some places where, culturally, unyenyekevu ambao unahitajika kwa kazi zingine za nyumbani sio unyenyekevu ambao unapatikana sana kati ya watu wetu..” Loosely translates to mean that Kenyan workers should be more submissive when working in certain places. Our government is most comfortable earning foreign exchange from the efforts of the labourer class, to whom they feel least responsible.

The institutional weakness is visible in the absence of any established or state-supported system for hiring of skilled professionals, whose skills are worth more per person. This cadre would of course require more government input and legal attention to their terms, but our interest has been more in the number going out rather than their value. Another example is the tech sector. The IT skill levels amongst Kenyan youth are world renowned, but rather than encourage techpreneurs, Kenya invites big tech firms to outsource their online monitoring to skilled cheap youth labour in Kenya. One such company, Sama was receiving over 10 US dollars per man hour from Facebook for these jobs and paid the workers less than 2 dollars an hour for the highly stressful work. Complaints about the conditions fell on deaf ears until an article about it appeared in ‘Time’ magazine in March 2022. After the exposé their wages were raised to $ 2.20 per hour, still a pittance, but an improvement only motivated by the western gaze, not our country’s perceived value of skilled labour. This mentality is replicated across trade in minerals, agricultural commodities, and fossil fuels all of which tend to be traded in their ‘raw’ form, bereft of any value addition.

Our greatest challenge as Africans today is our inability to understand our homeland’s value through people rather than through commodities, or the much-vaunted “natural resources”. It leads us to ape the behaviour of our exploiters in the way treat our own citizens. This is also apparent in the heritage sector. Anyone who visits the National Museums of Kenya and notices that we have an “Institute of African Studies” housed there. In 2013, the oldest known human burial site was ‘discovered’ in Panga ya Saidi at the coast. As soon as the remains were fully excavated, the National Museums of Kenya shipped them off to the National Center on Human Evolution (CENIEH) in Burgos, Spain ‘for further analysis’. We still needed the external gaze here, in this case to validate that we actually had civilized societies, burying our dead 78,000 years ago. Literature even refers to this find as a ‘discovery’ yet the remains were of a child, carefully buried by his family, who were presumably humans. Further afield, the fallacy of ‘African studies’ is robustly displayed by top American universities without a hint of irony on their websites. Harvard University claims to be “one of the world’s foremost centers of learning about Africa” in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Princeton is even bolder about its primitive extractivism, stating that “Africa is the continent where our future will be determined. The continent boasts an abundance of both cultural and natural resources and is home to some of the fastest growing economies in the world, making Africa a fascinating place to study.” On their ‘Program in African Studies’ webpage. Stanford University is the least bashful of the sample, sharing some decidedly fascist views from their faculty on their website like this gem from Prof. Sean Hanretta, a historian who studies Islam in West Africa; “Colonialism defined what it meant to be African.” Shared on their African studies webpage.

We African scholars need to find our compatriots a way out of this miasma where we constantly examine ourselves through the prism of Western eyes, beliefs, and thought patterns, thus making them our “peers” in the knowledge of our own identity and heritage. This is necessary because academia tends to be the ‘unquestionable’ vessel through which questionable ideas find their way into practice. There is no reason why for instance, a Kenyan can describe human interactions with an organism or even a culture particular to a certain part of his homeland and his work will be “peer reviewed” by some scholars born raised and working deep in the American Midwest (with all due respect to them). The Merriam-Webster definition of ‘peer’ is “one that is of equal standing with another”. Foreign scholars and institutions are not our peers or equals in knowledge about ourselves. It is imperative that we devise new networks and methods of developing our own knowledge of ourselves for the benefit of our societies. We are our only peers, and we must start acting accordingly.

Such articles are never meant to vilify the West, though many see them as such. They are simply calls for change, which necessarily must come from, and be driven by the global south, if it is to benefit mankind. The West and the Global north has no imperative whatsoever to change a structure that has served them so well since the days when their intentions were less than noble because there exists no inertia as strong as that visited upon any society by past successes.

The Stealthy, Surreptitious Second Coming of Western Colonialism in Africa.

In November 1884, European powers (represented by elderly white men) met in Berlin presuming to divide amongst themselves the large “cake” that was the African continent. It was a looting mission that later morphed into a political exercise, and the rest as they say, is history. An interesting footnote is that the conference lasted a whole three months until February 1885, indicating that the discussions must have been quite protracted, and probably interspersed with copious amounts of food, drink and debauchery (a feature of conferences that hasn’t changed much, over a century later!)

Fast forward to 21st Century Africa. The much-touted Africa Protected Areas Congress (APAC2022) has been held in Kigali, Rwanda. Myself and others have already written and spoken extensively about how “Protected areas” are actually “white spaces” in a majority black continent. During the colonial era, they were literally spaces set aside for the recreation of white people. In the post-independence era, the spectrum of users now includes black people, but they are still lily-white in terms of the paranoid, prejudiced, violent and intellectually stunted manner of their management. This mentality is the “white” identity of conservation practice in Africa today. The practitioners have made many attempts to mask this identity, by creating strange mongrels referred to as “conservancies” of various kinds, but the concept is the same. Annex land from indigenous African people who use it for their livelihoods and set it aside for the self-actualization of foreign elites. Africa is fabulously wealthy in natural resources, but we must ALWAYS remember that the value of the visible above ground resources is a mere fraction of what lies underneath. Sadly, the spectacular beauty of our wildlife, forests and rangelands makes them the perfect windowdressing for the cruel schemes laid out against us as a continent. The brutality of slavery and colonialism showed us the cruelty that exists within the matrix of western capitalism. Laws and regulations have obviously been written in the last 100 years, but it we must remember that colonialism was a capitalist enterprise and it would be naïve in the extreme to imagine that capitalism had somehow lost its cruelty. The new dispensation only required that they apply new and more sophisticated methods and voila! Enter the climate change/ carbon trade/ conservation cult. It’s a perfect vehicle because it is pervasive, running in a contiguous vein through corporations, governments, civil society and even global bodies like the UN. Cult leaders (read: conservation ‘icons’ like Goodall, Attenborough, et. al) have access to heads of state. Their greatest coup has been the so-called “30×30” plan, which is the ludicrous proposal that every country should put 30% of their land under “protected areas” by the year 2030 to conserve biodiversity. The “evil beauty” of this plan is that the plan has to be implemented in the global south, because there is no significant biodiversity gain to be made from expanding Regent’s Park in London or Central Park in Manhattan by 30%. Everything is primed and ready to go. The UN and governmental adoption of this plan smoothes out all the necessary regulatory hurdles, including tax breaks in both source and client states. Once that is done, now all you need is a major conference like APAC2022 where you can blow all the dog-whistles against indigenous people and give all the apocalyptic alarmist statements about Africa (with no reference to the west where the real environmental destruction has been for the last 100 years). First, you pick a country like Rwanda that has formally decided that their greatest role in Africa will be as a European foothold on the continent (remember the UK refugees’ caper). Then we convene conservation organizations, practitioners, their corporate funders and governmental enablers. After a few days of lip service, drink and debauchery, you come up with a closing statement that includes a huge carrot and little substance https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/africa/africa-protected-areas-congress-continent-gets-200-billion-conservation-fund-83955?fbclid=IwAR0Y6dvwCC9gFTJ-0e4WLFeFSSzqbGXR2QkkmQeFvAjvfCefxrbU83ZRdTg and everybody leaves struggling with flatulence induced by excitement over the impending windfall. One of the most strangest parts of this excitement is that very little of the largesse actually finds its way to indigenous Africans. Most of it goes to expatriates from the donor countries, while Africans at all levels from heads of state to village elders are swayed with breadcrumbs in the form of business class air tickets, accommodation in luxury hotels, alcohol and perdiem payment to attend meetings where they simply say ‘yes’ to everything. The key point to note about this so-called conservation fund is that it proposes a ‘network’ of a total of 8600 conservation areas covering a total area of 26 million square kilometers. This is a startling figure, given that it is an area more than twice the size of the US, and represents more than 80% of Africa’s land mass. How do these people subvert sovereign structures with such consummate ease? A simple tool known as “transboundary conservation areas”, conservation that purports to manage contiguous habitats across international boundaries. We then find ourselves in a strange situation where non-state actors enjoy powers unheard of in state agencies, with untrammeled reach across international boundaries. An example of this power is the Big Life Foundation that operates across the Kenya-Tanzania border, enjoying access that Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) and Tanzania National Parks (TANAPA) cannot have. This is the nature of the new colonies. They fly under the radar by not following known boundaries, and within countries they exist as conservancies that don’t exist in law, don’t pay taxes and don’t register lands in their names. As the host of the conference, Rwanda has been the first signatory on this project and is taking leadership, asking other African countries to sign. With all due respect to that Great Nation, I don’t think that the owner of 0.0065% of the protected areas in question should assume leadership of the same. This however reveals another well-practiced annexation technique ngof the conservation organizations. Eliminating individual opinions of Nations and people, by lumping them together into “projects” and “communities”. The colonists are here, again to stake a claim on our birthright. The other tried and tested technique is the relentless drive to evaluate our lands in terms of this strange thing they refer to as ‘carbon’. What most Africans don’t realize about ‘carbon’ credits, sequestration, sinks etc is that it is a tool for eliminating the natives from any discussions or calculations about the said land. They aren’t the fat old white men we see in the artists’ impressions of the Berlin conference. Many of them look like us, speak our languages, many are young, and many are women too, and they claim to be saviours. The methods and faces are certainly new, but the avarice and corruption remains unchanged, 137 years later. Despite myself, I must grudgingly acknowledge the historical correctness of holding the conference in Rwanda, part of what used to be German East Africa. Aluta Continua

Recognize and reject all violence in conservation

Seretse Khama Ian Khama posted this on 13 April 2022

“This was one of the largest if not the largest tusker in the country. An elephant that tour operators constantly tried to show tourists as an iconic attraction. Now it is dead.

How does it being dead benefit our declining tourism due to poor policies. Our tourism is wildlife based. No wildlife means no tourism, no tourists no jobs, and no revenue stream. Incompetence and poor leadership have almost wiped out the rhino population, and now this!”

This a quote from the immediate former president of Botswana, lamenting the recent killing of a particularly large-tusked elephant by white paying poachers (aka sport hunters) in his homeland. As expected, the comments section was filled with paroxysms of grief, accompanied by the smells and sounds of people breaking wind in consternation. His post above, illustrates that like 99% of African leaders, he is completely incapable of examining or understanding the value of our natural heritage outside the prism of entertainment and edification of white people. My home country, Kenya is a veritable intellectual vacuum in this regard. 99.5% of people in the conservation sector have zero understanding of the value of natural heritage. Out of the 0.5% who do, I am probably the only one who doesn’t work for the 99.5%

We in conservation have become prisoners of this is ridiculous ‘whiteness’. The best description of this malaise that I’ve heard was given by Darius Okolla, a Nairobi-based researcher; “Whiteness describes a paranoid society which cannot co-exist with nature without seeking to acquire it in some way”. The mindless bloodlust of sport hunters is just one of many symptoms of the disease, but there are many others, including the theft of elephant calves from the wild by “conservation” organizations who then hold them captive to entertain other paranoid clients for money. Another is the intellectually vacuous program KWS launched which seeks to get money from paranoia victims who want to “acquire” wildlife by paying to “name” animals after themselves. If we allow ourselves to think clearly, we will realize that the need to kill a bull elephant for his huge tusks comes from exactly the same mental place as the need to name him after yourself (because of his huge tusks). Do we now understand clearly why the biggest tusks in Amboseli belong to an elephant called “Craig”? Now examine all the policy arguments around conservation in Kenya. They are all centered around the needs of different centers of whiteness, namely the tourism industry, the hunting industry, and the “conservation” industry. These are all different facets of whiteness, each with its own methods and avenues of violence. The sport hunting industry is the most primitive facet of whiteness, and in some ways, the most honest, because they kill in broad daylight and until the rubbish they started speaking recently, they have never claimed to be interested in anything or anyone’s need, other than their own bloodlust. The tourism industry is the most intellectually stunted facet, because they wait for other people’s warped or childish dreams about Africa, then work very hard, doing their best to bring this nonsense to reality. The most devious and deliberately violent are the conservationists, most so because they seek to serve the interests of whiteness by expressly vilifying indigenous people, their livestock, and their livelihoods. They are also the most dishonest, because they claim to be altruists, doing all this for some strange faceless concept they call ‘nature’ that is somehow separate from human beings. Their hubris is only matched by their hypocrisy, and its normal to hear them cry over the violent death of an elephant and rejoice over the violent eviction of humans from their homes to make room “for wildlife” with which they have shared their homelands for millennia. That’s also why the people who constantly moan about the local population ‘threatening’ wildlife in Kenya are the same ones who went to ask the minister to allow them to hunt, and he actually formed a taxpayer-funded task force to look into that nonsense. They are the ones who imprison our political leaders and state authorities into parasitic relationships that facilitate their violence. Our authorities thus become their choirboys, singing their praises and mourning when they are challenged, either by natives, or their fellow pirates. This is the intellectual ditch Khama has fallen into. The killing of any African animal for sport is a brutal affront to our values as Africans. However, Khama thinks this is a tragedy because of the value of this animal to another set of “white” pirates who want to acquire it in a different way. If he and other African leaders truly understood conservation, they would know that the size of his tusks are about as important to us as the size of the ticks on his wrinkled backside. Aluta Continua!

The Native Getting Educated and The Ivy League Myth

As a young student, I was always fascinated by the ‘top’ universities and the erudite people who emerged from those August institutions. My first contact with Ivy league people was when I arrived at Mpala Research Centre in Laikipia in 1999 to commence my MSc research. I met students and faculty from Princeton University (which is a trustee of the research centre) and was reassured that they looked ‘normal’, with all the academic challenges and foibles that a Kenyatta University student like me had. After I finished my MSc, the administration were impressed enough with my work to offer me a job as resident scientist, which I took up with the alacrity of someone taking up a big break he got through hard work (I got a rude awakening later, but that’s a story for another day). As part of my job, I was assigned to supervise a group of Princeton undergraduates doing a senior field project, and sharpened my ecologist brain wanting to impress, especially because I thought I would be instructing some of the world’s sharpest young minds. I now laugh at my consternation when after mapping out clear and easy ecological transects for them, they strayed off into a neighbouring ranch and I got a call from the security personnel there that they were sunbathing topless on the research vehicle (they were ladies) and that the boss might be offended. Later on, I asked a postgraduate student from the same institution how these ladies could be so casual about their studies, and she couldn’t hide her amusement at my ignorance. “Grad school is competitive, undergrads get in because of money and name recognition”. I was stunned, but I remembered this when I saw the poor work they submitted at the end of their study. Being an aspiring lecturer (and a student of the late brilliant Prof. R. O. Okelo) I marked them without fear or favour, assuming that they would be used to such standards at Princeton. I was told that I couldn’t give them such low marks because they were supposed to qualify for Med school after their biology degrees. The next cohort included one serious student who I actually enjoyed instructing and she finished her course successfully. By that time though, I was getting restless and had started writing an academic and financial proposal for my PhD, and I finished it about 6 months after my student had gone back to the US to graduate. The then Director of Mpala, Dr. Georgiadis refused to let me do my PhD on the job, so I submitted my proposal to several conservation organizations, including the New York based Wildlife Conservation Society. I got a positive response from them (offering me a grant) which hit me with a strange mixture of feelings. First of all, I was elated at the prospect of starting my PhD, but I was completely baffled at the signature on the award letter. It was the undergraduate student I had supervised about 8 months earlier. An American undergraduate who had spent 2 months in Africa was somehow qualified to assess a PhD proposal on ecology of African wildlife written by an African MSc. holder. It was my first rude awakening to the racial prejudice that is de rigueur in African conservation practice. But I had to get my academic career moving and indulge my first taste of the ultimate luxury that my competence and work could afford me, which was the ability to say “NO”. It was with extreme pleasure that I wrote and signed my resignation letter from my job at Mpala, leaving it on the Directors desk.

Years later, after I finished my PhD and had a useful amount of conservation practice under my belt I attended the Society for Conservation Biology (SCB) conference in Sacramento, California where there was a side event featuring publishers from several Ivy league universities and I excitedly engaged them because at the time, Gatu Mbaria and I were in the middle of writing “The Big Conservation Lie”. I pointed out to all of them that there were no books about conservation in Africa written by indigenous Africans, but they were uniform in their refusal to even read the synopsis of what we had written. I later understood this when I learned that in US academia, African names as authors or references are generally seen as devaluations of any literature. From Sacramento, I made the short trip to Stanford University in Palo Alto, to give a seminar to an African Studies group. I felt honoured to be giving an academic contribution at an Ivy League university and I prepared well. My assertions about the inherent prejudices in African conservation practice were met with stunned silence by the faculty, many of whom are involved with conservation research in Africa. One bright spot in that dour experience was one brilliant Ph.D student in attendance who echoed my views and pointed out that these prejudices existed within academia as well. I later found out that he was Kenyan, His name is Ken Opalo and he now teaches at Georgetown University. Fast forward to today. The ‘Big Conservation Lie’ got published, and after the initial wailing, breaking of wind, gnashing of teeth and accusations of racism, Mbaria and I are actually being acknowledged as significant thinkers in the conservation policy field and our literary input is being solicited by different publications around the world. Now, the cultural differences between how European and American institutions treat African knowledge are becoming clear (certainly in my experience). I have been approached by several European institutions to give talks (lectures), contributed articles and op-eds (to journals and magazines) and one book foreword. Generally, the approach is like this;

“Dear Dr. Ogada, I am_______ and I am writing to you on behalf of________ . We are impressed with what you wrote in _____ and would appreciate it if you would consider writing for us an an article of (length) on (topic) in our publication. We will offer you a honorarium of (X Euros) for this work, and we would need to receive a draft from you by (date)….”. Looking forward to your positive response…”

When inviting me to speak, the letters are similarly respectful and appreciative of my time. The key thing is the focus on and respect for your intellectual contribution.

Publications from American Ivy league schools typically say;

“Dear Dr. Ogada, I am __________, the editor of __________. We find your thoughts on _______ very interesting and we are pleased to invite you to write an essay of________(length) in our publication. Previous authors we have invited include (dropping about 6-8 names of prominent American scholars).

The entire tone of the letter implies that you are being offered a singular privilege to ‘appear’ in the particular journal. It is even worse when being asked to give a lecture. No official communication, just casual message from a young student saying that they would like you to come and talk to their class on__________(time and date on the timetable). No official communication from faculty or the institution. After doing that a couple of times, I realized that the reason these kids are so keen to have an African scholar speak to them and answer all their questions is because they need his knowledge, but do not want to read his publications, or (God forbid) have an African name in the ‘references’ section of their work

European intellectuals seem to catching on to the fact that knowledge and intellect resides in people, not institutions. That is why they solicit intellectual contributions based on the source of an idea they find applicable in the space and time. Name recognition doesn’t matter to them, which is why they seek people like Ogada, who doesn’t even have that recognition in Kenya. The US elite schools still place this premium in institutions, which is why whenever an African displays intellectual aptitude, those who are impressed don’t ask about him and his ideas, but where he went to school. They want to know which institution bestowed this gift upon him.

For the record, I usually wait about a week before saying ‘no’ to the Ivy league schools. Hopefully, they read my blog, they will improve the manner in which they approach me, or stop it altogether.

Aluta Continua

Anatomy of a Paranoid, Prejudiced Cult…

Many of my friends, particularly those from outside the conservation sector have been puzzled by the silence that has followed the release of the “Stealth Game” report by the Oakland institute https://www.oaklandinstitute.org/stealth-game-community-conservancies-devastate-northern-kenya. This, my friends, is because you people mistakenly imagine that conservationists in Kenya are normal, functional human beings. They are NOT, and the rational ones are fewer than 5%, the scientific threshold for statistical significance. For those of us who know them well, we can read and interpret this silence to a high level of accuracy. First of all, rest assured that everyone who need to see the report has done so, including government officials at both county and national level. I personally forwarded it to an official at the highest levels of government, and the response I got was “thank you”, at least admitting to have seen it. Interestingly, two senior county government officers also forwarded the report to me, leaving me wondering what exactly they see as their role in the whole scandal, as opposed to mine as an individual. The silence is only in the public sphere. I have direct contacts in a lot of private spaces where there is a lot of wailing, gnashing of teeth and breaking of wind as a result of this report.

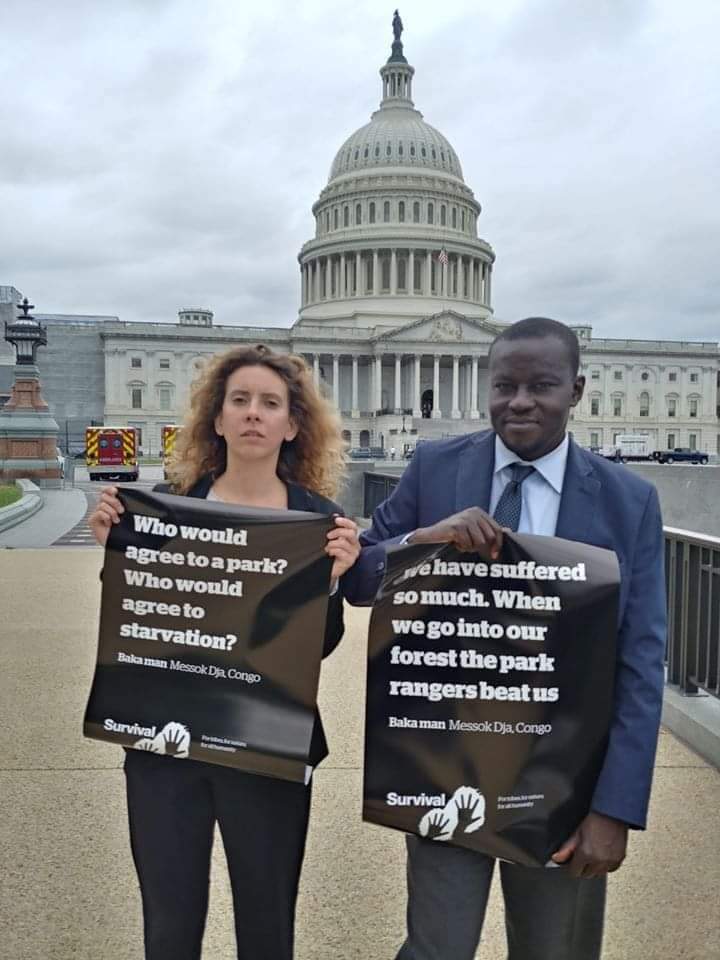

The key point we all need to understand here is that people are in trouble- bringing to mind that uniquely American expression about faecal material hitting a fan and splattering everyone in the vicinity. Here’s why; A couple of years ago, a few colleagues and I visited the US house of representatives in Washington DC to present a memorandum on abuses of human rights in central Africa by WWF under the guise of conservation, an issue we also brought to the attention of various European legislatures. It has taken time, but the cosh has come down on WWF, culminating in a Senate hearing earlier this year, which has severely tightened the screws on them. First of all, the consternation that has greeted the report is disingenuous, because none of this information is new- it is simply saying the same things that myself and a few colleagues have been pointing out since 2016.

The conservation sector in Kenya routinely dismisses any questions from black Africans and the consternation is because the report is coming from an American institution, and cannot be dismissed on racial grounds. An amusing anecdote I’ve heard from one of the conservation groups is “This is just the usual noise from Mordecai Ogada”… then another member says “No, its from the Oakland institute in the US” then all hell breaks loose with people crying “Oh my God, what are we going to do??”. In a separate forum, a senior participant (who obviously hadn’t read the report) dismissed it as lacking credibility “Since the only source of such information is Mordecai Ogada (again!!??). Another participant pointed out that it was the result of over 2 years’ research and she changed tack attacking the author Anuradha Mittal on her racial and family background. The bizarre thing is that this woman is also from the same racial background! Many people will find this bizarre, but I don’t. Our conservation sector is so steeped in racial and ethnic prejudice that it’s shameful. Apart from dealing with people who don’t want to hear me because I am black, I’ve had to deal with indigenous Kenyans who routinely tell me to keep off wildlife issues in Northern Kenya because I am a Luo from Western Kenya!

The key issue of rights violations is studiously avoided by conservationists to a ridiculous degree. I’ve seen conversations where The Nature Conservancy’s communications director is asking a whole group of conservation professionals how they can “Counter Mordecai Ogada’s narrative” (Again!!??). A couple of years ago Northern Rangelands Trust hired Dr. Elizabeth Leitoro as a “director of programs” and one of the key expectations was that she should somehow “control” Mordecai Ogada (yes, Again) since over 20 years ago I was her intern when she was the warden at Nairobi National Park. She asked to meet me, and my son was patient enough to sit with us as we talked. Later on, she launched a racial attack on me and my family on social media to defend NRT (she deleted it and blocked me, but I still have a screenshot and NRT got rid of her) This shows the neurosis bedeviling conservation in Kenya. They will scream, shout and make personal attacks and noise about everything EXCEPT the problem at hand. Secondly, they are obsessed with appearances, so you will never hear a word said by any of the foreigners who run that show. It will always be ill-advised, ill prepared, but well-paid locals who will come out in robust (if somewhat foolish) defense of their captors. Right now the national government, county governments, and conservation organizations are all tongue tied, because they don’t know how to dismiss criticism from the US, where their lifeblood funding comes from. USAID is the biggest conservation funder in Kenya, and the biggest grantee is NRT, which gives them God-like status here. All other conservation voices like Kenya Wildlife Conservancies Association (KWCA) or Conservation Alliance of Kenya (CAK) which receive small change grants cannot say a word against their “leader” NRT. That is why 5 days later, CAK claims to be “still reading the report”. They are waiting to see which way the wind is blowing before they make any noise or break any wind in defense of their fellow Kenyans.

Mark my words, these people have colossal reach- that’s why even GoK has said nothing. There was a major press conference in Nairobi on 17th November about this report, and all major media houses in Kenya were there, but the story has been “killed”. They have a HUGE PR machine, and if anything in the report was untrue, they’d have torn it to shreds. Their bogeyman, Mordecai Ogada (frankly I’m abit flattered!) is not in the picture, so they cannot point fingers at me anymore, and now need to address the ISSUES. I’m informed that some heads have already rolled. They are big, but not big enough to kill the story in the US public policy space. WWF learned that the hard way .There shall be wailing, there will be hypertension, some hyperacidity, diarrhea and other stress-related illnesses, but it looks (and smells) like change is coming.

This silence isn’t the golden kind, it’s the silence of sick, trembling cowards caught in a big lie. I have nothing to add to the “Stealth Game” report, but wherever and whenever I will be asked to say something about it, I will not let anyone get away with trying to look shocked. I will always state just how I told them about this injustice 5 years ago, but it never mattered then, truth be told, because I am black.